| |

BACK

TO TABLE OF CONTENTS

A theoretical investigation of chemical

kinetics - (v)

Potential energy surfaces

(1) Introduction

(2) Some results from experiments and calculations

(2-1) The direction

of attack and separation

(2-2) Attractive

and repulsive surfaces

(2-3) Classical

trajectories (i.e. trajectories obtained through equations of classical

mechanics)

Potential energy surfaces

(1) Introduction

The potential energy surface of a reaction may be defined as

'the potential energy as a function of the relative positions of all

the atoms taking part in the reaction'.

For example, a collision between a hydrogen atom (H) and a hydrogen

molecule (H2), the potential energy surface is the plot of the

potential energy for all relative locations of the three hydrogen nuclei.

Detailed calculations show that the approach of an atom along the H-H axis

requires less energy for reaction than any other approach, so initially

we confine our attention to a collinear approach where a hydrogen atom

HA approaches an HB-HC molecule in the

direction of HB-HC, heading towards HB.

Two parameters are required to define the nuclear separations:

-

The HA-HB separation, RAB, (= infinite

at the start of the of the encounter, equilibrium bond length at the end

of a successful of the encounter)

-

The HB-HC separation, RBC, (= equilibrium

bond length at the start of the of the encounter, infinite at the end of

a successful encounter.)

as illustrated in Fig. 1 below.

Fig. 1: The definition of RAB and RBC.

The total energy of the three-atom system depends on their relative

separations, and can be found through molecular modelling techniques (e.g.

by doing a molecular orbital calculations). The plot of the total energy

of the system against RAB and

RBC is

the potential energy surface of this collinear reaction, and is illustrated

in Fig. 2a below.

Note that:

-

This surface is normally depicted as a contour diagram, as illustrated

in Fig. 2b.

-

When RAB is very large, the variation in potential energy

represented by the surface is that of an isolated H2 molecule

as its bond length is altered, as illustrated in Fig. 2c. Similarly for

when RBC is very large at the end of a successful encounter.

Fig. 2 (a) The potential energy surface for the

H + H2 -> H2 + H reaction when the atoms are constrained

to be collinear.

Fig. 2(b) The contour diagram (with contours of

equal potential energy) corresponding to the surface in Fig. 2(a). Re

marks the equilibrium bond length of an H2 molecule (strictly,

it relates to the arrangement when the third atom is at infinity).

Fig. 2(c) The molecular potential energy curve

for the hydrogen molecule showing the variation of the energy of the molecule

as the bond length is changed. Re marks the equilibrium bond

length of an H2 molecule.

The paths that are available to the atoms may be deduced from the shape

of the potential energy surface, as these corresponds to paths of least

potential energy. (The actual path of the atoms in the course of the encounter

depends on their total energy, the sum of their kinetic and potential energies.)

Let us illustrate this for the simple case of a hydrogen atom HA

is approaching a hydrogen molecule, HB-HC, to form

HA-HB and HC. Referring to fig. 3a, let

us investigate three way how this (at least theoretically) can be accomplished:

(Path A): One approach could be to let the HB-HC

bond length remain constant during the initial approach of HA.

In this path, the potential energy rises to a high value as HA

is pushed into the molecule, and then decreases sharply as HC

breaks off and separates to a great distance.

(PATH B): An alternative reaction path can be imagined in which

the HB-HC bond length increases at an early stage

of the approach of HA (i.e. while HA is still far

away). This path takes the system through a region of a high potential

energy in the course of the encounter (compare with path C).

(PATH C): This is the path of least potential energy, and corresponds

to RBC lengthening as HA approaches and begins

to form a bond with HB. The HB-HC bond

relaxes at the demand of the incoming atom, and the potential energy climbs

only as far as the saddle-shaped region of the surface, to the saddle

point marked C‡. In this path of least potential

energy, the atoms take a route up the floor of the valley, through the

saddle point, and down the floor of the other valley as HC recedes

and the new HA-HB bond achieves its equilibrium length.

This path is the reaction coordinate we met in the earlier section discussing

the activated complex.

Thus, through Path C, we can now make contact with the activated complex

theory of reaction rates. In terms of trajectories on potential surfaces,

the transition state can be identified with a critical geometry such that

every trajectory that goes through this geometry goes on to react, i.e.

the saddle point C‡.

NOTE: Paths A and B are theoretically feasible, provided, the molecules

have sufficient initial kinetic energy to take the three atoms past the

regions of high potential energy in the course of the encounter.

Fig. 3a: Various trajectories through the potential

energy surface shown in Fig. 2. Path A corresponds to a route in which

RBC is held constant as HA approaches; path B corresponds to a route in

which RBC lengthens at an early stage during the approach of HA; path C

is the route along the floor of the potential valley.

Fig. 3b: The transition state is a set of configurations

(here, marked by the line across the saddle point) through which successful

reactive trajectories must pass.

(2) Some results from experiments and calculations

To travel successfully from reactants to products the incoming molecules

must possess enough kinetic energy to be able to climb to the saddle point

of the potential surface.

The shape of the surface can be explored experimentally by changing:

-

The relative speed of approach (by selecting the beam velocity), and,

-

The degree of vibrational excitation

and observing whether reaction occurs and whether the products emerge in

a vibrationally excited state.

Such work allows us to answer some important questions: For example,

what is better, to smash the reactants together with a lot of translational

kinetic energy or to ensure instead that they approach in highly excited

vibrational states? (In other words, is trajectory Fig. 4c, where the HBHC

molecule is initially vibrationally excited, more efficient at leading

to reaction than the trajectory in Fig. 4a, in which the total energy is

the same but has a high translational kinetic energy?)

Fig.. 4: An illustration of some successful (marked with an *) and

unsuccessful encounters: (a) C1* corresponds

to the path along the foot of the valley; (b) C2* corresponds

to an approach of HA to a vibrating HBC molecule,

and the formation of a vibrating HAB molecule as HC

departs. (c) C3 corresponds to HA approaching a non-vibrating

HBC molecule, but with insufficient translational kinetic energy;

(d) C4 corresponds to HA approaching a vibrating

HBC molecule, but still the energy, and the phase of the vibration,

is insufficient for reaction.

(2-1) The direction of attack and separation

(i) Direction of attack:

-

Fig. 5a shows the results of a calculation of the potential energy as an

H atom approaches an H2 molecule from different angles, the

H2 bond being allowed to relax to the optimum length in each

case. The potential barrier is least for collinear attack, as we assumed

earlier. (But we must be aware that other lines of attack are feasible

and contribute to the overall rate.)

-

In contrast, Fig. 5b shows the potential energy changes that occur as a

Cl atom approaches an HI molecule. The lowest barrier occurs for approaches

within a cone of half-angle 30o surrounding the H atom. The

relevance of this result to the calculation of the steric factor of collision

theory should be noted: not every collision is successful, because not

every one lies within the reactive cone.

Fig. 5a: An indication of the anisotropy of the

potential energy changes as H approaches H2 with different angles

of attack. The collinear attack has the

lowest potential barrier to reaction. The surface indicates the potential

energy profile along the reaction coordinate for each configuration.

Fig. 5a: An indication of the anisotropy of the

potential energy changes as H approaches H2 with different angles

of attack. The collinear attack has the

lowest potential barrier to reaction. The surface indicates the potential

energy profile along the reaction coordinate for each configuration.

Fig. 5b: The potential energy barrier for the

approach of Cl to HI. In this case, successful encounters occur only when

Cl approaches within a cone surrounding the H atom.

(ii) Direction of separation:

-

If the collision is sticky, so that when the reactants collide they orbit

around each other the products can be expected to emerge in random directions

because all memory of the approach direction has been lost.

-

A rotation takes about 1 ps, so if the collision is over in less than that

time, the complex will not have had time to rotate and the products will

be thrown off in a specific direction.

For example, in the collision of K and I2, most of the products

are thrown off in the forward direction. This product distribution is consistent

with the harpoon mechanism because the transition takes place at long range.

In contrast, the collision of K with Cl2 leads to reaction only

if the molecules approach each other very closely. In this mechanism, K

effectively bumps into a brick wall, and the KI product bounces out in

the backward direction. The detection of this anisotropy in the angular

distribution of products gives an indication of the distance and orientation

of approach needed for reaction, as well as showing that the event is complete

in less than 1 ps.

(2-2) Attractive and repulsive surfaces

Some reactions are very sensitive to whether the energy has been predigested

into a vibrational mode or left as the relative translational kinetic energy

of the colliding molecules. For example:

-

If two HI molecules are hurled together with more than twice the activation

energy of the reaction, then no reaction occurs if all the energy is translational.

-

For F + HC1 -> Cl + HF, the reaction is about five times as efficient when

the HCl is in its first vibrational excited state than when, although HCl

has the same total energy, it is in its vibrational ground state.

The origin of these requirements can be found by examining the potential

energy surface: Figure 6a shows an attractive surface in which the

saddle point occurs early in the reaction coordinate. Figure 6b shows a

repulsive

surface in which the saddle point occurs late. A surface that is attractive

in one direction is repulsive in the reverse direction.

Fig.6a: An attractive potential energy surface.

A successful encounter (C*) involves high translational kinetic energy

and results in a vibrationally excited product.

Fig. 6b: A repulsive potential energy surface.

A successful encounter (C*) involves initial vibrational excitation and

the products have high translational kinetic energy. A reaction that is

attractive in one direction is repulsive in the reverse direction.

(i) The attractive surface (Fig. 6a)

-

Observations:

-

If the original molecule is vibrationally excited, then a collision with

an incoming molecule takes the system along C. This path is bottled up

in the region of the reactants, and does not take the system to the saddle

point.

-

If, however, the same amount of energy is present solely as translational

kinetic energy, then the system moves along C* and travels smoothly over

the saddle point into products.

-

Conclusions:

-

Reactions with attractive potential energy surfaces proceed more efficiently

the energy is in relative translational motion.

-

Moreover, the potential surface shows that once past the saddle point the

trajectory runs up the steep wall of the product valley, a then rolls from

side to side as it falls to the foot of the valley as the products separate.

In other words, the products emerge in a vibrationally excited state.

(ii) The repulsive surface (Fig. 6b).

-

Observations:

-

On trajectory C, the collisional energy is largely translational. As the

reactants approach, the potential energy rises. Their path takes them up

the opposing face of the valley, and they are reflected back into the reactant

region. This path corresponds to an unsuccessful encounter, even though

tl energy is sufficient for reaction.

-

On C* some of the energy is in the vibration of the reactant molecule and

the motion causes the trajectory to weave from side to side i the valley

as it approaches the saddle point. This motion may be sufficient to tip

the system round the corner to the saddle point and then on to products.

In this case, the product molecule is expected to be in an unexcited vibrational

state.

-

Conclusions:

-

Reactions wit repulsive potential surfaces can therefore be expected to

proceed more efficiently if the excess energy is present as vibrations.

(2-3) Classical trajectories (i.e. trajectories obtained through

equations of classical mechanics)

A clear picture of the reaction event can be obtained using classical

mechanics to calculate the trajectories of the atoms taking place in a

reaction.

-

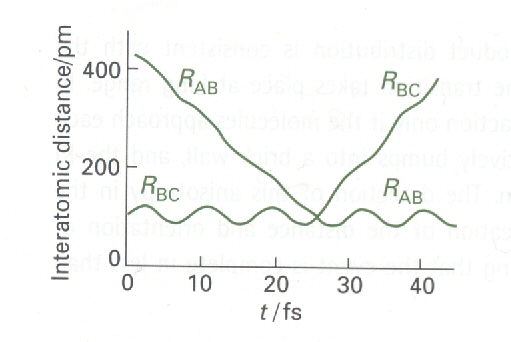

Fig. 7a shows the result of such a calculation of the positions of the

three atoms in the reaction H + H2 -> H2 +H, the

horizontal coordinate now being time and the vertical coordinate the separations.

This illustration shows clearly the vibration of the original molecule

and the approach of the attacking atom. The reaction itself, the switch

of partners, takes place very rapidly and is an example of a direct-mode

process. The newly formed molecule shakes, but quickly settles down to

steady, harmonic vibration as the expelled atom departs.

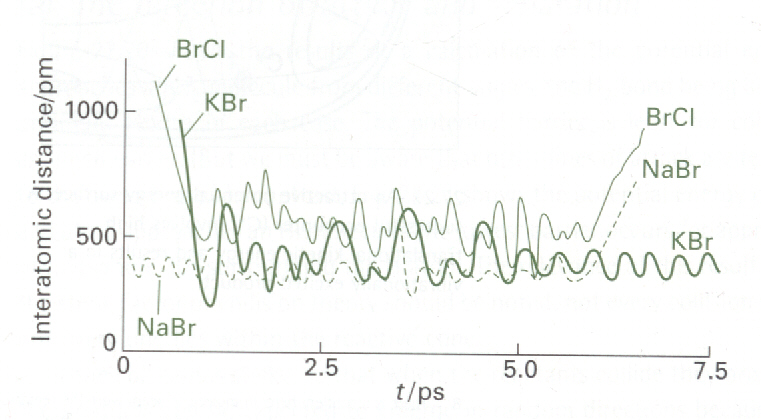

-

In contrast, Fig. 7b shows an example of a complex-mode process, in which

the activated complex survives for an extended period. The reaction in

the illustration is the exchange reaction KCl + NaBr -> KBr + NaCl. The

tetraatomic

activated complex survives for about 5ps, during which time the atoms make

about 15 oscillations before dissociating into products.

Although this kind of calculation gives a good sense of what happens during

a reaction, its limitations must be kept in mind.

-

In the first place, a real gas-phase reaction occurs with a wide variety

of different speeds and angles of attack.

-

In the second place, the motion of the atoms, electrons, and nuclei is

governed by quantum mechanics. The concept of trajectory then fades and

is replaced by the unfolding of a wavefunction that represents initially

the reactants and finally the products.

Nevertheless, recognition of these limitations should not be allowed to

obscure the fact that recent advances in molecular reaction dynamics have

given us a first glimpse of the processes going on at the core of reactions.

Also, one is to note that such studies are now extermely feasable using

very basic computer software and hardware (see CH407).

Fig. 7a: The calculated trajectories for a reactive encounter

between HA and a vibrating HBHC molecule

leading to the formation of a vibrating HAHB molecule.

This direct-mode raection is between H and H2 (M. Karplus et

al., J. Chem. Phys., 43 (1965) p.3258)

Fig. 7b: An example of the trajectories calculated for a complex-mode raection,

KCl + NaBr -> KBr + NaCl in which the collision cluster has a long lifetime.

(P. Brumer and M. Karplus, Faraday Disc. Chem. Soc., 55 (1973)

p.80).

BACK

TO TABLE OF CONTENTS

|